By Eric Sagara, Emmanuel Martinez and Ike Sriskandarajah / October 8, 2016

By Eric Sagara, Emmanuel Martinez and Ike Sriskandarajah / October 8, 2016

Fire is as common to Western states as the drought-dried shrubs that feed the flames. This month marks the 25th anniversary of the Oakland Hills Firestorm in the San Francisco Bay Area that destroyed about 3,000 homes and killed 25 people. At an estimated $1.5 billion in losses – $2.7 billion in today’s dollars – it remains the country’s most costly wildfire to date.

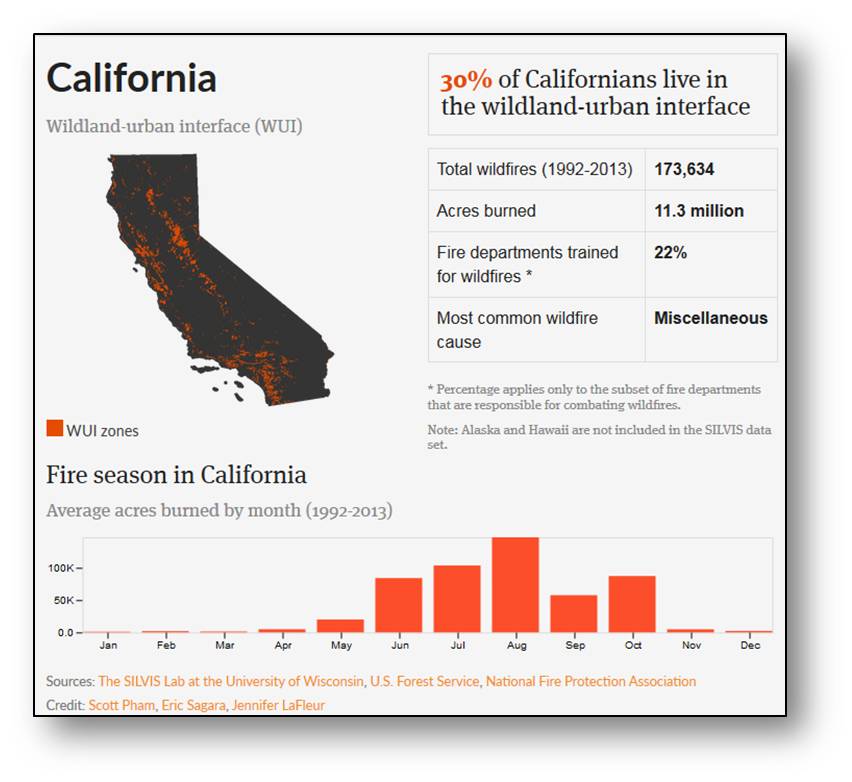

Wildfires, long considered a problem exclusive to the West, now threaten many other parts of the country as extreme weather becomes more commonplace and more people live in areas at risk for wildfire.

Jodi Aldridge never thought her Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, home was vulnerable. But on the evening of March 16, 2013, one of her co-workers at a Chili’s restaurant pointed to smoke in the distance, near where she lived.

Aldridge, 39, rushed from work to her condo complex, hoping to rescue Puck, her pug puppy.

“It was insane,” she recalled. “You could literally watch the fire jump from bush to bush and building to building.”

Aldridge said she “ran up the steps of what I thought was my building, not realizing my building was completely gone.”

What began as a grass fire eventually destroyed more than 100 condos.

Aldridge never found Puck. All she managed to retrieve was a beach towel and part of a plate her son had made for her for Mother’s Day.

In South Carolina, where Aldridge lives, nearly 2 out of every 3 people live in regions classified by researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison as wildland-urban interface, or WUI – areas where homes and wildland meet and where the stakes and potential for wildfires are higher. From 1992 to 2013, the state saw more than 78,000 wildfires.

Nationally, more than a third of new homes built since 2000 are in WUI areas. What has happened, wildfire historian Stephen J. Pyne wrote in 2008, is that we’re “leaving natural growth alone and then stuffing the openings with combustible structures.”

Using multiple government databases and satellite images to examine the threat of wildfires across the country, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting found that since 1990, 8.5 million more homes are in WUI areas. The major reason is that the border between nature and urban development is constantly shifting as new homes push out into the wilderness.

More than half the wildfires between 1992 and 2013 occurred in Southern states, including Texas, Georgia, Florida and North Carolina. Fires there typically are smaller, with an average size of 27.6 acres. Fires in Western states are roughly six times larger.

In California, the Sand Fire tore through more than 41,000 acres of land in a matter of days in late July, destroying 18 buildings and killing one man.

But as climate change continues to bring warmer, drier conditions to most of the country, many experts agree that wildfires will be both larger and more frequent.

And those frequently tasked with battling the flames – local fire departments – often don’t have the training to fight wildfires.

Nationally, only about a third of fire departments that cover WUI areas have the specialized training and 30 percent have the necessary equipment, according to a 2011 study from the National Fire Protection Association. Most of these departments must rely on help from other state, local and federal agencies during a wildfire.

In some Southern and Eastern states, the amount of land in WUIs is striking. In Connecticut, for instance, more than half the population lives in WUIs.

If those areas become drier, as predicted, they will be more susceptible to wildfires.

According to a report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, “because temperatures and precipitation levels are projected to alter further over the course of this century, the overall potential for wildfires in the United States, especially the southern states, is likely to increase as well.”

In many areas that have lost houses to wildland fires, homeowners return to build again on land that they already own. It is unusual for local officials to have the authority to stop people from rebuilding, but they can require that new homes be built to fire-resistant standards.

The exact requirements vary, but building codes usually call for roofs and decks to be made of fire-resistant materials and for a buffer of space between homes and trees and shrubs.

Rebuilding following a fire is a slow process, according to a national study by the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Only a quarter of homes are replaced within the first five years after a fire.

The study also found that new home construction within fire perimeters happened much faster than the rebuilding of lost homes. In some states such as Texas and Oklahoma, new construction in these areas also outpaced development in areas untouched by fire.

It is easier for local authorities to control building standards than to prevent people from a building a home in a WUI.

“Building in the wildland-urban interface is fraught with peril and not just because homes and lives could be lost. The chances of sparking a wildfire is greatest near roads and homes,” said Patrícia M. Alexandre, one of the study’s authors.

“This is one big reason we worry about more building, because people aren’t just building in a fire-prone environment; they increase the fire probability in that region,” she said.

She said new home construction in these areas indicates that people may not be aware of the risk. Builders may not be concerned with the issue because they are not the ones living there.

“In flood zones, real estate agents are required to tell you about flood hazard, but we don’t do that with fire hazard,” Alexandre said.

In 2013, a group of 19 elite firefighters died and 130 homes were destroyed in the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona. Three years later, Yavapai County officials say, about half the homes lost have been rebuilt or are under construction.

Vito Austin, a general contractor in Yarnell, said he’s helping rebuild the community by constructing new homes in burned areas. At the same time, he’s able to turn a profit. County officials have made it easier to rebuild in Yarnell, he said.

After the Yarnell Hill Fire, Yavapai County extended the amount of time residents had to rebuild before being having to pay fees associated with new development – from one year to three.

“The county has given you the opportunity to waive the assessment fees,” Austin said. “You know, so therefore, it’s easier to pull the permit and go ahead with your rebuilding.

“This is the land of opportunity.”

Any new development there must meet stricter building codes, such as using fire-resistant materials and creating defensible space and access points for emergency vehicles. The local fire district has done some work to clear vegetation, but officials have taken no additional steps to reduce the risk of wildfire in the area.

Wildfire is such a serious threat in some areas that the insurance industry is rethinking how it covers homes – or whether it will. Some companies are no longer insuring in WUIs. Others are raising their rates. A few insurance companies are even employing private firefighting forces to protect expensive homes. American International Group Inc., better known as AIG, offers to private clients a wildfire protection unit that can be dispatched to protect homes during a wildfire.

Voters in Flagstaff, Arizona, took matters into their own hands, passing a $10 million bond in 2012 to thin U.S. Forest Service land outside the city. The goal was twofold: Thinning prevents catastrophic firestorms and the flooding and mudslides that can come later. Fires not only strip the landscape of plants that slow erosion and water runoff, but also seal the soil so it won’t absorb moisture.

Flagstaff’s response followed a long history of battling wildfires. And while $10 million might seem like a lot of money, it is minimal compared with the costs of fighting fire and recovering from it. The 2010 Schultz Fire, which started just north of Flagstaff, burned more than 15,000 acres. It cost $12 million to fight. Recovery, which continues six years later, has surpassed $140 million.

More than a thousand residents from nearby housing developments were evacuated. No homes were lost to the fire, but the burned hillsides could not hold back heavy rains that came later, causing erosion and flooding. Ash-laden water gushed down hillsides, causing extensive damage to homes.

“The biggest threat for the city of Flagstaff is wildland fire,” said Skyler Lofgren, a wildland fire supervisor for the Flagstaff Fire Department. “We’ve had a whole social change in Flagstaff from ‘cutting any trees is bad’ to ‘now we need to take out some trees so we don’t lose all of our trees.’ ”

For decades, land policy in the United States called for suppression of wildfires, preventing the natural process that clears overgrowth. As a result, forests became so thick that when a fire sparked, it could easily jump from tree to tree.

Now, fire officials near Flagstaff are thinning the ponderosa forest that rings the city of 70,000.

After the Windsor Green Fire that destroyed Jodi Aldridge’s home in South Carolina, the county took steps to bolster communities against wildfire. It strengthened outdoor burning restrictions and updated building regulations. The Horry County Council passed a tax increase to add fire department staff.

The fire “absolutely opened people’s eyes” to make changes, said Brian Van Aernem, a battalion chief and spokesman for Horry County Fire Rescue. “We’ve seen some wildfires since, but they spread slower and were more contained.”

In 2009, President Barack Obama signed the Federal Land Assistance, Management and Enhancement Act, or FLAME Act, which requires land management agencies to come up with plans to reduce fuel. The U.S. Forest Service manages 192 million acres, 58 million of which are at risk to hazardous fires – an area larger than Washington state.

A federal audit released in August found that the Forest Service has missed its goals for reducing wildfire fuels for the past two years and that it needs to develop tools to make better decisions about where to concentrate its efforts.

Figuring out where to focus treatment is “not just a matter of where on a map do you need to do treatment,” said James E. Hubbard, the Forest Service’s deputy chief for state and private forestry.

“Part of the difficulty was having the common land data to make determinations,” he said. “We need to know the condition of the forest. We need to know the topography of the land.”

All those factors help determine where the biggest risks are. In the meantime, fighting wildfires has used up the much of the agency’s resources. In fiscal year 2015, the Forest Service spent $2.6 billion – more than half its entire budget – on preparing for and fighting wildfires. In 1995, firefighting was 16 percent of the agency’s budget.

At nearly every level of government, battles are being waged about how to best deal with the wildfire threat.

The federal government sued New Mexico over a 2001 state statute that gave counties the power to thin Forest Service lands in cases of emergency. A federal judge ruled last year that the state could not claim control over federal lands.

Last month, the Federal Emergency Management Agency withdrew $3.5 million in grant money from the city of Oakland and the University of California, Berkeley to clear vegetation on 458 acres of land in the Oakland Hills, including some of the areas that burned in the 1991 firestorm.

The funding was to be used to remove invasive vegetation – eucalyptus, pine and acacia trees. It was pulled as part of a settlement in a lawsuit filed against FEMA by the Hills Conservation Network, a nonprofit organization of area homeowners. The organization is not opposed to thinning, but opposes the plan to remove large trees because they provide windbreaks. The group also opposed the use of herbicides to prevent regrowth.

FEMA will reallocate some of the funds to nearby thinning projects planned by the East Bay Regional Park District. The remaining money will be used elsewhere in the state, the agency said in a written statement.

Stephen J. Pyne, the wildfire historian, said that unless there’s coherent and coordinated policy that looks at development and forest management, these problems will be difficult to solve.

“Otherwise, you’re just in the whack-a-mole mode and you’re not going to win,” Pyne said. “In cities, every fire you put out is a problem solved. In wildlands, every fire you put out is a problem put off.

See the original article with more information and interactive features at Reveal News, here.